Living today in an Ireland in which we do not have any significant alternative to a hegemonic right-wing press and broadcast media, it is difficult to imagine a time when there was a vibrant antidote to counteract the conservative propaganda of the national newspapers. But over a period from 1898 to 1916 and spanning a range of movements including advanced-nationalist, feminist, cooperative and socialist, their newspapers, journals, pamphlets and newsletters planted progressive ideas in the minds of their readers and often explicitly primed and prepared them for revolutionary action. It is worth understanding how this was achieved by looking at the content of these publications. In this article the Labour press will be examined, with the other movements to be examined in later articles.

Writing in 1937, Stephen Browne SJ said ‘…the history of the Irish Labour Press may be said to begin with the first appearance in 1898 of Connolly’s Workers Republic. Indeed, though the workers’ cause had been advocated in the past by such leaders as Fintan Lalor and Michael Davitt, the labour movement proper begins with James Connolly, who may fairly be described as the first Irish labour leader pure and simple.’ Browne was correct in that final point, but also in linking Connolly back through Michael Davitt to James Fintan Lalor, as Connolly himself frequently acknowledged. Browne might have completed the list of influences – from Lalor and his contemporaries, Thomas Davis and the Young Irelanders, back again to the anti-sectarian United Irishmen of the 1790s. That list of influences explains the three main strands to Connolly’s ideology – nationalism, republicanism and socialism, to which he consciously added advanced-feminism. And it was his core socialist republicanism that defined his nationalist outlook, lifting it away from the inward-looking Catholic nationalism of many of his contemporaries and allowing him to develop and express his progressive internationalism. All of this he brought to the pages of his newspapers, his pamphlets and his public speaking, in the process educating and informing his audience.

But throughout his career it was always primarily the interests of his class – the working-class – that occupied his thoughts. Those who criticised his move (as they mistakenly saw it) towards militant separatism and the company of nationalists between 1914 and 1916 as a profound and regrettable change ignore his long-standing linkage of the unhappy plight of the working class in Ireland with British colonialism, and of workers internationally with the rapacious greed of capitalist imperialism. His appreciation of James Fintan Lalor’s position on the subject – that social questions and the national issue should be regarded as complimentary – is revealed in his writings from 1896 on, and shows that his later actions in forming a revolutionary coalition were inevitable. Prior to establishing his newspaper The Workers Republic in 1898, Connolly’s political stance was published in the pages of advanced-nationalist papers. From the earliest days he had established contact with militant nationalists, especially through his work on the preparations for the centenary of the United Irishmen’s 1798 revolution.

The first issue of The Workers Republic appeared on the 13th of August 1898, just two days before the massive gathering for the dedication of the foundation stone of the proposed Wolfe Tone monument. On page two, writing under one of his pen-names, Spailpín, Connolly tells his readers – ‘We are Republican because we are Socialists, and therefore enemies to all privileges; and because we would have the Irish people complete masters of their own destinies, nationally and internationally, fully competent to work out their own salvation.’

Page one included a trenchant criticism of Irishmen for fighting in the four corners of the world ‘under any flag, in anybody’s quarrel, in any cause except their own’. Page three carried an article on the long hours and low pay of the men who worked for the Dublin Tram Company – it would be 18 years before the owner of that company, William Martin Murphy, would get in his final retaliation in by leading the charge for Connolly’s execution. On page five, there is an attack on ‘Home Rule Journalists and Patriots’. In an article on page 6, signed Saoirse, Connolly advises Dublin Castle of the socialists’ intention to get rid of the capitalist system. There are several articles and references to Wolfe Tone throughout the paper, including on landlordism and revolution. The last of the eight pages is made up of a statement of the objects and aims of the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP), and a series of advertisements for the party’s open air meetings ‘Every Sunday Evening, 7.30. Foster Place.’, for an appeal for funds for the ISRP, for Connolly’s seminal pamphlet ‘Erin’s Hope: the End and the Means’, and only one commercial advertisement – for ‘A Good Reliable Bicycle for the Cheapest Possible Price’ at M. J. Lord.

On page one of the following week’s issue, Connolly reports on a speech made by Lord Mayor Tallon at the ‘98 Commemoration banquet – ‘Poor Wolfe Tone. Lived, fought, and suffered for Ireland in order that a purse-proud, inflated wind-bag should exploit your memory to his own aggrandisement’. The story continues on page six – ‘I am told it passed over as well as such things usually do. A number of speeches were delivered by gentlemen who did not mean what they said. As far as I can learn they all got safely home. There is nothing more to relate concerning the dinner unless to remark that there were no working men there. It was a middle-class dinner, in a middle-class restaurant, for middle-class people’. Connolly was not inclined to take prisoners when reporting on the words or actions of the rich and powerful, and it is not hard to imagine the delight with which reports like this must have been received among the working-class readers. This was part of the style of the newspaper, the mixing of serious content with caustic and highly humorous and very subversive comment.

On September 3rd the paper carried a translated reprint from L’Irlande Libre titled Socialism and Irish Nationalism which ends with a clear enunciation of Connolly’s position on both the failings of the concept of bourgeois revolution, and the necessity of forging alliances with willing partners to create a sustainable revolution. The ending is also prophetic. “Having learned from history that all bourgeois movements end in compromise, that the bourgeois revolutionists of today become the conservatives of tomorrow, the Irish Socialists refuse to deny or to lose their identity with those who only half understand the problem of liberty. They seek only the alliance and the friendship of those hearts who, loving liberty for its own sake, are not afraid to follow its banner when it is uplifted by the hands of the working class who have most need of it. Their friends are those who would not hesitate to follow that standard of liberty, to consecrate their lives in its service even should it lead to the terrible arbitration of the sword.”

Two weeks later The Workers Republic carried the first installment of Labour in Irish History under another Connolly pen-name ‘Setanta’. The finished book would eventually to be published 12 years later, in 1910, on Connolly’s return from the USA. The paper was starting to receive more advertising now. On page eight a firm called Daly & Co. of Blackburn advertised two products, Daly’s Chimney Cleaner, and Daly’s Pile Salve – hopefully not with interchangeable lids! The following issue carried the first article in the paper by Maud Gonne which was on ‘Irishmen and the British Army’.

In October, the paper ceased production until its reappearance the following May. Finance was always a problem, and the paper several times went into hibernation if there was an election to be fought. In August 1899, the paper issued a four page ‘Wolfe Tone Supplement: the Social-Revolutionary’, which included ‘Industrial Progress and Revolution’ by Arthur O’Connor, ‘The Self-Catechism of a Rebel’ by John Mitchel and an article on ‘Fenianism and Continental Revolution’. In September, the paper announced a move to new larger premises at 138 Upper Abbey Street, ‘To include a shop, a clubroom, a large lecture hall, and two separate rooms for the printing outfit which now includes two printing presses’. Two weeks later the paper advertised the fact that lectures were now being held in the Workers Hall every Sunday, admission free.

From January 1901 the style of the paper changed. It was now more dense and carried reprints of previously published articles, as well as current reports. It was not as easy or as enjoyable a read. It reverted back to the original size and form in July 1902. A month later it carried the announcement of ‘Our American Mission’, that being Connolly’s planned trip to America to raise funds by way of a lecture tour. The funds he raised and sent back were dissipated by the time of his return. Connolly, with a family to feed, and no funds to keep the party or the presses going, went back to America where he remained until 1910.

When he eventually returned it was to more fertile territory than he had left due to James Larkin’s efforts over the preceding four years to organise workers into a trade union. With the Irish Transport and General Workers Union (ITGWU) in place, there was now a relatively solid base from which to work. In June 1911 The Irish Worker newspaper appeared, edited by Larkin with Connolly’s active participation, and it enjoyed very substantial sales from the start. In June 1911 its circulation was 26,000. By September it had reached a staggering 95,000 copies. Its circulation fluctuated but remained healthy. It was an important weapon in the hands of the labour movement before and during the lock-out of 1913, and crucial in the formation and instruction of the Irish Citizen Army. When Larkin left Ireland to raise funds in the USA in 1914 he left Connolly effectively in control of the ITGWU, and commanding the Irish Citizen Army

In 1915, the Irish Worker was suppressed by the government, and to fill the vacuum, Connolly re-launched The Workers Republic. His newspaper would play an important role in providing coverage of the Army’s activities, training articles etc., and also as a link with the activities of the Irish Volunteers. The first issue, on the 29 May 1915, carries the message, ‘The Army and Reserves will parade on Sunday at Liberty Hall to take part in the May Day procession to the Park. All ranks are called out for the muster. By Order.’. On page 8 the paper carried accounts of military happenings so as ‘to enlighten and instruct our members in the work they are banded together to perform’. In ‘Notes on the Front’, page one, July 3rd 1915, there is a review of “From a Hermitage”, a pamphlet by P. H. Pearse, including this comment ‘We find ourselves in agreement with most of the things he says…and are surprised to find him so wisely sympathetic on the struggles of the workers with which we are most closely identified.’

A week later, under the heading ‘Ourselves and Our “Allies”’, the paper offered ‘heartiest congratulations to the Larkfield Team of the Irish Volunteers who won the tournament at St. Enda’s Fete last Sunday’. The paper was by now providing extensive coverage of the Citizen Army, with training notes on a wide variety of military topics from issue to issue. A series of articles during 1915 drew on revolutionary tactics used in, for instance; Revolution in Belgium (12th June), Revolution in Paris 1830 (July 3rd), while an article on June 19th dealt with the story of the Alamo, which the revolutionary HQ – the GPO and surrounding streets – would emulate less than a year later.

The issue of 15 April 1916, nine days before the revolution would start, carried a poem by C. de. Markievicz :

‘The Call’

‘Do you hear the call in the whispering wind?

The call to our race today,

The call for self-sacrifice, courage and faith

The call that brooks no delay.’

On the same page is an announcement of a ‘Solemn Hoisting of the Irish Flag at Liberty Hall on Sunday April 16′.

The last issue of the Workers Republic of the 22 April, two days before the Revolution, carried an image of a harp above and below the poem “Eire” by Maeve Cavanagh. The authorities in Dublin Castle would have been reassured, however, by the first lines of the cover article ‘Notes on the Front’ – ‘As this is our Easter edition, and we do not feel like disturbing the harmony of this season of festivity…’. But this last issue of The Workers Republic also carried an editorial titled ‘Labour and Ireland’ in which Connolly described the hoisting of the new flag of the republic over Liberty Hall – “So closely had the crowds been packed that many thousands had been unable to see the ceremony on the square, but the eyes of all were now riveted upon the flag pole awaiting the re-appearance of the Colour Bearer. All Beresford Square was packed, Butt Bridge and Tara Street were as a sea of upturned faces. All the North Side of the Quays up to O’Connell Street was thronged, and O’Connell Bridge itself was impassable owing to the vast multitude of eager, sympathetic onlookers… At last the young Colour Bearer, radiant with excitement and glowing with colour in face and form, mounted beside the parapet of the roof, and with a quick graceful movement of her hand unloosed the lanyard, and

THE FLAG OF IRELAND

fluttered out upon the breeze.

Those who witnessed that scene will never forget it. Over the Square, across Butt Bridge, in all the adjoining streets, along the quays, amid the dense mass upon O’Connell Bridge, Westmoreland Street and D’Olier Street corners, everywhere the people burst out in one joyous delirious shout of welcome and triumph, hats and handkerchiefs fiercely waved, tears of emotion coursed freely down the cheeks of strong rough men, and women became hysterical with excitement… As the first burst of cheering subsided Commandant Connolly gave the command, “Battalion, Present Arms”, the bugles sounded the General Salute, and the concourse was caught up in a delirium of joy and passion.

In a few short words at the close Commandant Connolly pledged his hearers to give their lives if necessary to keep the Irish Flag Flying, and the ever memorable scene was ended.”

Two days later, Connolly would oversee the unfurling of that flag of the Irish Republic over the GPO as the revolution began. Nineteen days later he was dead, a battle-wounded prisoner, already dying from gangrene, murdered by firing squad in Kilmainham Gaol, and with his death the authentic voice of labour in Ireland was silenced.

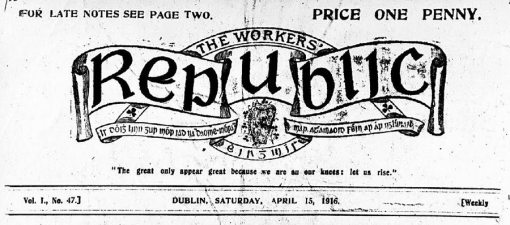

We do not need armed revolution in Ireland today, but we certainly need a revolution in thought and spirit, a revolution that, as always, begins in the imagination. But where can we find that organ of the mass media that will present to the people of Ireland alternative ideas to consider, propose better solutions to problems and issues of national importance, show us the lessons of the past that can guide us towards more informed judgements and help us make better decisions? The answer is bleak. In the Ireland of the 21st century that organ of the mass media does not exist. But it cannot be beyond the means of today’s free citizens to create a modern version of The Workers’ Republic, Irish Freedom or The Irish Citizen, online. Here is a start – the masthead of the penultimate edition of James Connolly’s The Workers’ Republic.